I’ve used Linux for several years. My introduction was with Kali Linux, but it turned out not to be the ideal starting point, so I left the ecosystem for a few years. When I next tried, it was Zorin OS, one of the most beautiful Linux distributions. Ever since, I’ve used Fedora, Debian, Arch, Ubuntu, and Manjaro. Today, Linux Mint is my daily driver.

However, NixOS has become popular, especially for its declarative configuration model, which enables reproducible systems and atomic rollbacks. So for a whole week, I decided to try it out as my primary distro. If nothing else, it changed how I think about Linux.

The death of the snowflake system

How my Linux install stopped being a historical accident

In my experience of using Linux, after a while, my computers gradually become a result of everything I’ve ever done on them. Even the packages I install for simple one-off tasks linger for far longer than they’re needed. Over time, configuration files are edited, overwritten, and only half-reverted. So, even when I have two installs of the same distro, they can end up being significantly different.

NixOS checks this kind of drift. The distro treats the system as something you generate, rather than something you constantly modify. It makes your root filesystem reproducible at any time from a configuration. I was coming from distros where /etc is sacred, so this initially felt unsettling.

It took me 5 years to learn not to make these Linux mistakes

Linux isn’t hard—you just need to dodge these traps.

However, it all clicked the moment I realized I could rebuild the system, where no part of the new build relied on past actions. The system simply didn’t care about past experiments or mistakes, and only reflected what I explicitly described. This one-week experiment was the first time I experienced a Linux distro that was more of a defined system than a personal artifact.

Configuration as logic, not ritual

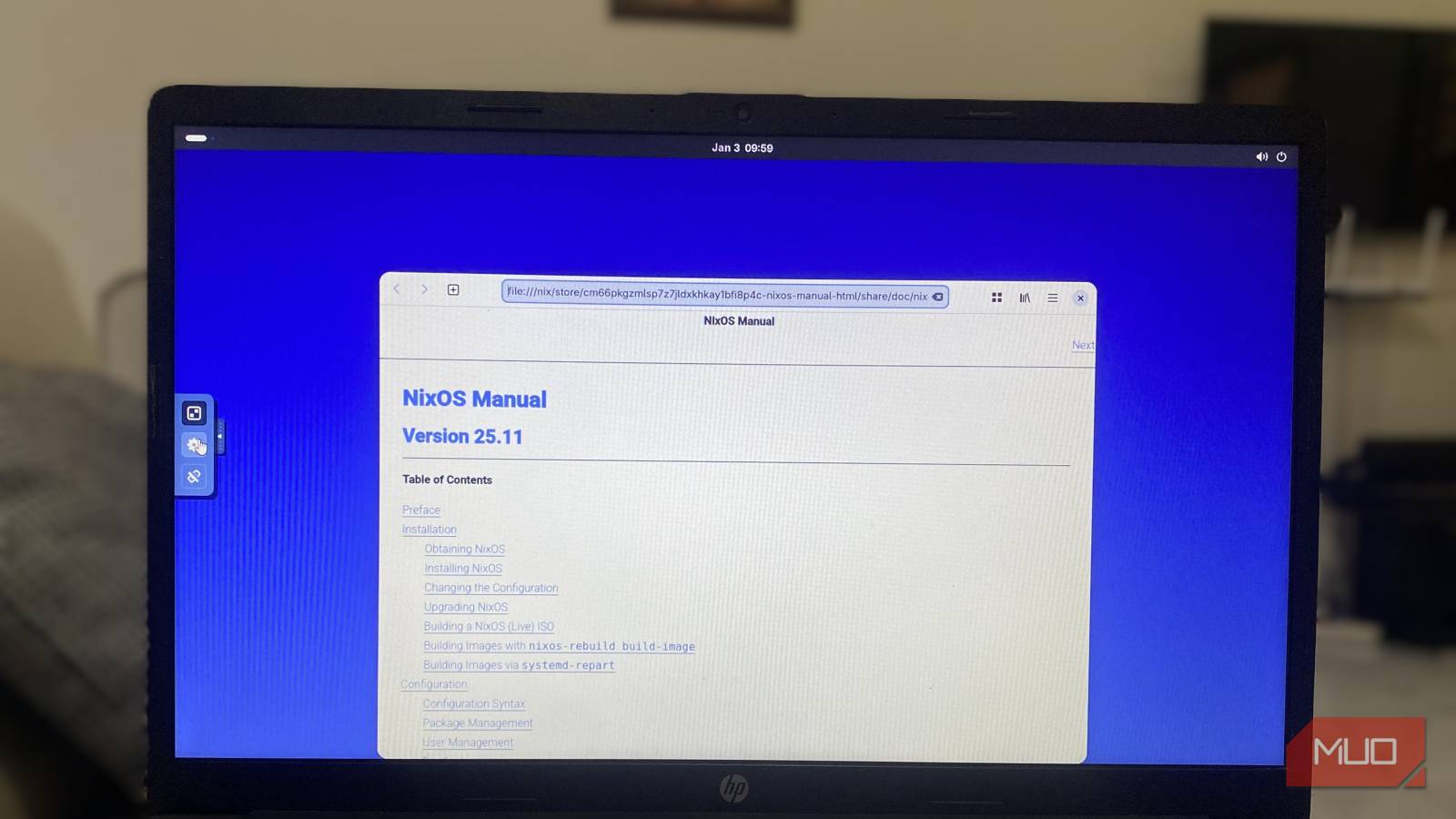

Learning to think in Nix instead of bash

The biggest shock I got, especially as someone who had tried several Linux distros, was realizing my existing Linux instincts were often wrong. I was constantly researching commands to manually patch configuration files and install missing dependencies, only to find out this wasn’t effective on NixOS.

For instance, when a service isn’t working, I might run the command sudo nano /etc/nginx/nginx.conf, change a line, and the problem would be fixed. But with NixOS, any such changes will either be ignored or eventually wiped away. The only true fix is to change the services.nginx options in configuration.nix and rebuild. You are practically changing the logic that defines the system to fix a problem.

This initially felt complex. I was used to simple edits and the familiar patterns. But NixOS’s language describes relationships, options, and outcomes. It gives precision, and after a few days, I started to appreciate it. I was intentionally enabling services and declaring dependencies rather than assuming them. It’s easier to understand why a process works and fix it from the configuration when it doesn’t work.

Breaking the OS stopped being stressful

How generations and rollbacks changed update anxiety

In just a week of using NixOS, I broke it more than once. But what I found surprising was that breaking it mattered so little. None of my bad configurations or failed rebuilds left the system in a damaged state, and I always had the previous working version intact and ready to boot.

Generations on NixOS fundamentally changed how I see and use Linux. A system rebuild creates a complete, bootable version of the OS. I could go back when anything went wrong, rather than have to troubleshoot a broken system. It’s like an advanced kind of Windows System Restore, where the entire system state (kernel, drivers, apps, configs) is saved, and the system is mathematically guaranteed to be exactly as it was. There are no snapshots to configure, and it removes guesswork from troubleshooting.

It changed the way I approach updates. They became reversible rather than commitments. But the greatest impact was that I became more willing to experiment, enable services, or try newer kernels. I was no longer avoiding change because I needed stability; I could easily undo changes.

Development environments without system pollution

How NixOS solved dependency hell without containers

I was surprised to notice how global installs started to feel wrong. But this only made sense because tools and libraries on NixOS can exist only where they’re needed. They don’t have to live on the system permanently.

This also meant that tools existed when I entered a project shell, and when I left, they ceased to. Using nix-shell or similar environments instantly feels different from virtual environments or version managers. Every project has its own reality, and nothing lingers or pollutes the system.

With Flakes (Nix’s reproducible package format), I was able to explicitly lock versions. When I combined this with binary caches, it felt very deliberate; compared to Docker, it was a lighter and more integrated approach. It was also cleaner than traditional setups, and my system wasn’t accumulating development baggage.

Fixing systems by changing definitions, not files

Throughout my experience, /nix/store was impossible to ignore. It initially felt hostile because paths are long, immutable, and unfamiliar. But the moment I realized this was an intentional setup, everything changed. I wasn’t supposed to edit anything in the store. Fixes don’t happen inside the filesystem. To troubleshoot, I adjusted definitions and rebuilt.

This was a sharp contrast to what I was used to on several other Linux distros, where I would edit files, restart services, and hope the changes would stick. For the first time in my Linux experience, I realized that when problems are tied to declared intent rather than hidden state, they are easier to reason through. After this experiment, I may not stick with NixOS as my daily driver, but traditional distros now feel noticeably messier.